“Trees and plants depend on the weather to flourish but I make my own weather, yea I transport it with me.” - Og Mandino

Recent reports have shown that high blood pressure is associated with negative outcomes from COVID-19.

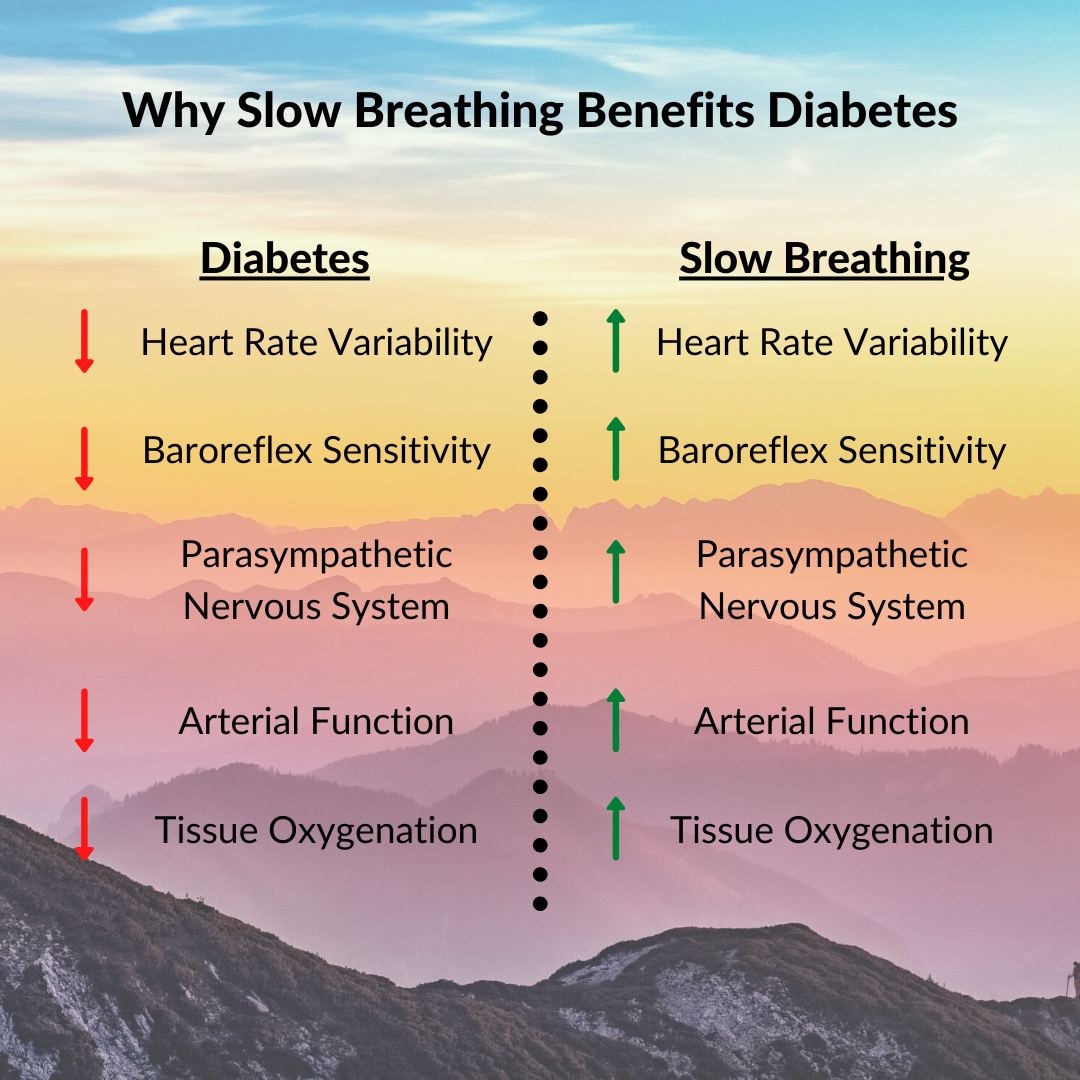

As people with diabetes, we already knew we were at higher risk when it comes to COVID-19. But, anywhere from 40%-80% of diabetics suffer from hypertension. That, on top of our compromised immune systems, is why we have to be more vigilant than ever with our health and well-being.

Thus, keeping our blood pressure under control should be a primary focus during these uncertain times.

A 2019 Meta-Analysis Shows Significant Reductions in Blood Pressure

I say this often, but meta-analyses are my favorite studies to read. They synthesize findings from all of the scientific literature on a particular topic in an easy-to-follow format.

The one I’m sharing this week looked at slow breathing and blood pressure:

Device and non-device-guided slow breathing to reduce blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Published in Complementary Therapies in Medicine, August 2019

On average, they found that slow breathing reduced systolic blood pressure by 5.62 mmHg. Slow breathing reduced diastolic blood pressure by 2.67 mmHg.

Additionally, the longer participants practiced, the more significant the reduction in blood pressure. For example, in the studies where subjects practiced slow breathing for more than 200 minutes per week, the average drop in systolic blood pressure was 14 mmHg.

These improvements are significant. Blood pressure reductions of these magnitudes have been shown to reduce the overall risk of cardiovascular death. Obviously, there are no studies explicitly looking at COVID-19 yet. Still, it seems safe to assume that these reductions would be beneficial, especially if you have diabetes.

Breathing as a Complementary Therapy

Slow breathing is not a cure-all. As the name of this journal implies (Complementary Therapies in Medicine), it is complementary, not a replacement. But, slow breathing is free and has no adverse side effects, so why not use it as another way of controlling your blood pressure, stress, and anxiety during these unsettled times?

In good breath,

Nick

P.P.S. Happy Mother’s Day to all of the amazing moms out there!